SECURITY

How safe is Uzbekistan? After an eleven-day, solo trip around the country, I’m firmly convinced that it is safe. In fact, I felt safer there than in many European countries. A country where there are police officers on almost every street corner is not an ideal place to live, but it is perfectly safe for tourists. Due to the attitude of the authorities it is also friendly to visitors. They even have tourist police, who can be seen everywhere (dark green uniforms, white booths, though these are often empty). The task of these policemen is to help tourists, and in theory they are supposed to speak English. And while they are not always able to provide you with simple information, they are always friendly. If you find yourself in a conflict with local people (which I didn’t experience), they are expected to help the tourists.

VISA AND COMPULSORY REGISTRATION

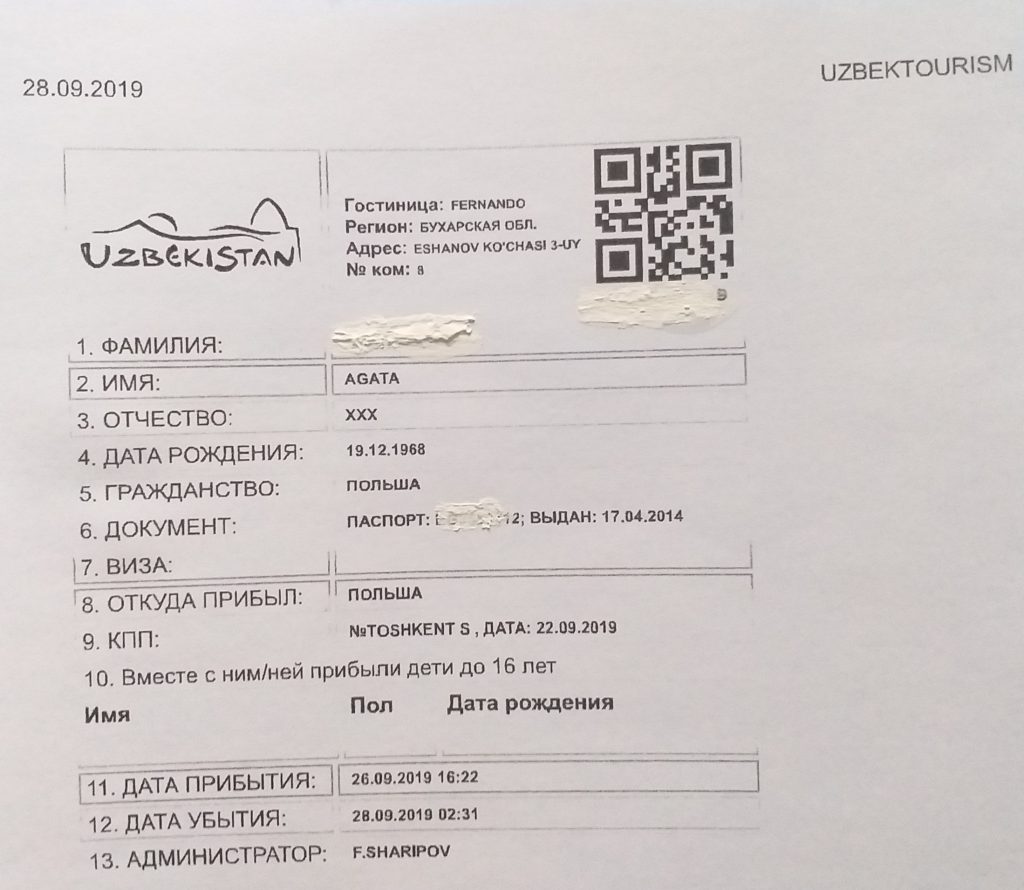

In 2019, the Uzbek government lifted the visa requirement for the citizens of 45 countries, including all the EU Member States. What they did not do is lift compulsory registration. In theory, it is the duty of every hotel or pension to provide guests with registration cards. Nevertheless, if you stay at cheaper hotels or pensions, you should make sure that the owner or manager registers you and provides you with tiny registrations slips (Russian: прописка). Do not lose these under any circumstances, since you may be asked to produce them when you are leaving the country. You can be fined up to USD 1,000 for not having registration cards. While some border guards don’t always check registration cards, or just glance at them, sometimes – as in my case – they go through them meticulously. Fortunately I had all the slips except one – I had spent one night on the train. Following the advice of other travellers, I kept the ticket and so I had no problems. This means that it can be a problem if you stay in private houses (or sleep rough). In this case you will have to go the office and register your stay on your own.

COMMUNICATION

English is spoken in some hotels, though the further you go from Tashkent the harder it gets. Apart from hotels, it is hard to communicate in English. Waiters and taxi drivers know some basic words and expressions, but it’s much easier to communicate in Russian (or a mixture of both). However, you may also encounter people, especially in Khiva, who don’t speak any foreign language.

TRAINS are cheap, quite clean and rather punctual. Tickets are not sold at the railway stations, but in nearby buildings. Passengers are not allowed not enter the station unless they can produce a valid ticket. You have to arrive at the station at least 30 minutes before your train is due to leave. Tickets can also be purchased at travel agencies or ordered in some hotels, obviously with commission. I asked the receptionist at my hotel to buy tickets for me and I paid USD 91 for a set of tickets on the route TASHKENT – SAMARKAND – BUKHARA – URGENCH – TASHKENT (including the cheapest couchette from Bukhara to Urgench and a second class sleeping car from Urgench to Tashkent), which seemed a reasonable price. Only later did I realise that the commission accounted for two-thirds of the cost. However, all the trains that I took looked full (apparently, you have to reserve a seat, no standing), so I wouldn’t recommend buying tickets just before you want to go, especially in high season. For three or four people, taking a taxi from one city to another may be a cheaper option, but possibly not a safer one. Roads in Uzbekistan are in poor condition and the style of driving is absolutely crazy.

Trains will not get you to Khiva or Shahrisabz. From Urgench to Khiva you can travel by bus, trolleybus or taxi. As far as Shahrisabz is concerned, the only option is a private or shared taxi from Samarkand. For a round trip I negotiated the price of UZS 250,000 (around USD 27), for two people the rate will be slightly higher.

- From Bukhara to Urgench: a cheap couchette/Z Buchary do Urgenczu – tania kuszeta

- From Urgench to Tashkent: a sleeping car/Z Urgenczu do Taszkentu – sypialny

- From Urgench to Khiva by bus/Autobus z Urgenczu do Chiwy

TAXIS are cheap, as long as you agree on the price in advance and that you haggle hard. Taxi drivers prey on the naivety of tourists from the west, who can be ready to pay USD 10 from the airport in Tashkent to a hotel in the city centre. However, the airport is near the centre and the regular price is the equivalent of USD 2.5 – 3. In Bukhara, a taxi driver was demanding USD 20 for the trip from the railway station to the centre, where the standard price would be closer to USD 3.5 – 4.5. Generally speaking, it is better to negotiate prices in Uzbek so’ms, since rates in dollars are already inflated. Sometimes you might even find yourself settling arguments between taxi drivers, who are at each other’s throats fighting over customers.

In Uzbekistan, every vehicle whose driver offers you a ride can serve as a taxi. Drivers usually wait for potential customers in front of airports, railway stations in large cities, hotels or just in the street. If you ask a hotel receptionist to call a taxi, they will call an acquaintance with a car. In fact, there are not many yellow, legal taxis – I took one only once. It is quite common to just flag down cars on the road – if the driver is going in the same direction they will probably drive you for a small fee (though you should never expect to be given a free lift!) Seasoned travellers, such as Erika Fatland, the author of an engrossing and very informative book “Sovietistan: A Journey Through Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan” claim that this means of transport is safe, even for solo female travellers.

- Flagging down in Tashkent/Okazją po Taszkiencie

STYLE OF DRIVING

Uzbeks drive fast and with abandon, though not as perilously as, for example, Georgians. In Georgia I saw every driver as a potential threat. Uzbeks seem to be eager to push pedestrians away so that they don’t block the road. In side streets they never stop for pedestrians – they may try to go round them ( the only problem is you never know which way round they are going to go…) However, in busy city centres, cars give way to pedestrians on zebra crossings (which the Georgians never do). The only road I travelled on between cities – from Samarkand to Shahrisabz – is in a terrible condition.

- From Samarkand to Shahrisabz by taxiTaksówką z Samarkandy do Szahrisabz

CURRENCY AND PRICES

The days when you had to carry around cash in plastic bags are luckily over. Nowadays Uzbeks use banknotes of 10,000, 50,000 and 100,000 soms. That’s a lot of zeros! It’s easy to get mixed up, especially to confuse the UZS 1,000 and 10,000 banknotes as they are similar colours. I tried to be careful with higher amounts, but one time I handed over UZS 30,000 instead of 3,000 when paying for a large bottle of water, and I paid UZS 10,000 instead of 1,000 to use the toilet – the shopkeeper was honest, but the bathroom attendant less so and I realised the mistake later while paying for something else.

You can usually pay for hotel rooms in American dollars, though the receptionists may give you the change in soms. Taxi drivers also accept dollars (but be careful – they cheat!). Cheap hotels often don’t accept cards, or at least not the cards that are popular in Europe, such as Visa.

In the bazaar in Khiva, vendors give prices in…. euros. In my wallet I had four currencies (soms, dollars, some Polish zlotys and Turkish liras), but no euros. It was no problem though, as I paid in dollars.

In general, Uzbekistan is not friendly to people who are used to paying by card. There are not many cash machines either, and if you do run across one, it usually doesn’t work.

Examples of prices:

A small bottle of mineral water: UZS 1,500 – 2,000

A large bottle of mineral water: UZS 2,500

A teapot for one person: UZS 2,000 – 10,000

A cup of coffee: UZS 3,000 – 25,000. Watch out! A cup of coffee can cost more than lunch.

Sometimes there are no prices on the menu or there are only the prices of the main dishes.

Entrance tickets for tourist attractions: from UZS 4,000 to 40,000 (Registan in Samarkand is the most expensive). Prices usually range from UZS 10,000 to 25,000.

TOILETS

They are not difficult to find. The price is fixed: UZS 1,000. Most of them are squat toilets. Usually they are not clean, there is no toilet paper, and sometimes no water. Restaurants usually have a washbasin outside. At the railway stations toilets are free of charge, whereas at the tourist attractions you usually have to pay.

FOOD AND CUISINE

Uzbek cuisine is high-fat and based on meat. Pilau, the national dish, varying by region, consists of rice, meat (usually mutton), small pieces of onions and carrots, sometimes raisins and – last but not least – oil. It is well-spiced, not hot, but I found it definitely too fatty. Another typical local dish is shashlik, well grilled and spiced, delicious, though also fatty.

What I liked most in Uzbekistan was a kind of dried cheese – khan sausage cheese (it looks like a huge sausage) often served for breakfast and added to salads. I also recommend delicious kefir and tomatoes, which taste much better than what you get in European supermarkets. A tomato salad, usually mixed with cucumbers is served in every restaurant. If it’s not on the menu, they may be eager to prepare it on special order. As for dessert, I highly recommend pakhlava (baklava).

For breakfast, cheap, family-run hotels usually serve some cheese and cold meats (which can put you off eating meat), followed by grilled eggs with sausages or fried potatoes, plus fresh fruit and biscuits. Usually it is not served as a buffet, but is portioned out.

- Traditional Uzbek cuisine/Tradycyjna uzbecka kuchnia

- Cheap eateries in Chorsu Bazaar in Tashkent/Garkuchnie na bazarze Chorsu w Taszkiencie

- Sweets in Siab Bazaar in Samarkand/Słodycze na Bazarze Siabskim w Samarkandzie